Last month I stepped onto the Alaska Airlines jet in Seattle late on a Sunday morning while taking my first business trip since the start of the pandemic. It felt good to get out of the crowd forming in the C Gate cluster at the end of the terminal. Not only was it my first business trip but the crowd was easily the largest I’d been in over a year and my mind set is still definitely “crowds=danger.” I settled into my seat happy to be away from the throng of humanity. Eventually a businessman from Midwest settled into the seat next to me. He was on the return trip home after joining some friends for a golf trip in California and spending a couple days in Seattle where he’d grown up. Somehow in the pre-flight small talk he decided that the best topic to chat with me about was cryptocurrency. “Are you in yet?”, he asked, “because Bitcoin is the future.” Now, let me be clear this blog isn’t about cryptocurrency. It’s about inflation which was where the businessman headed next expressing his concern that the $1.9 trillion American Recovery Plan Act was going to stoke inflation. This event wasn’t the first time in the last couple of months that someone has asked me about inflation associated with increasing government debt in support of repairing the COVID ravaged economy. I figured if multiple people are asking me about a topic then it will likely make a good blog post. So, let’s talk about inflation from an economic sense (I will leave talking about inflation from an investment perspective to the team at APCM).

What is inflation?

Strictly speaking inflation is a measure of how much more expensive a set of goods and services has become over a certain period (typically a year). It is simply the rate at which prices are increasing and we feel it through each dollar buying less than the year before.

Why do we care about inflation (and why is too much inflation bad)?

The most common reason that we care about inflation is because periods of high inflation are extremely destabilizing to an economy. A high rate of inflation creates a self-reinforcing cycle of increasing prices because when prices are increasing rapidly then the consumer mindset becomes “buy now because it will be more expensive tomorrow.” When we buy because of a fear of prices increasing, we increase demand for a product which in turn (going back to Econ 101) causes prices to rise. The rise in prices reinforces the psychology to “buy now.” The U.S. has not experienced a severe bout of inflation since the 1970s, but we have seen this inflationary psychology affect specific asset classes at certain points over the last 50 years. The 1999-2000 Tech Bubble and the 2006 Housing Bubble are localized asset class bubbles that most people are familiar with. I’m not quite old enough to remember the inflation of the 70’s, but I do remember the horrifically high interest rates and recessions that it took to squash the 70’s inflationary cycle. Those were not easy days in the King household.

Inflationary cycles tend to be very damaging for holders of cash (savers) because the purchasing power of their cash declines. However, these cycles can be good for the holders of hard assets if those assets don’t get caught in the popping of a bubble. And they can be good for workers, in the short run, as they tend to drive wages permanently higher.

Why is a little bit of inflation good?

While inflation sounds like a terrible thing it’s a critical component of our economy because it helps keep people spending. How likely would you be to buy a home if its price never went up? Think about how much of the psychology of buying a home depends on the idea that you get to keep the increase in price. In most home markets your home equity rises largely because of inflation and paying off your mortgage. Real dollar price increases in home values are relative rare in many markets and without the effect of inflation your home purchase would be a money loser after paying property taxes, upkeep, and interest on your mortgage.

Where is inflation now?

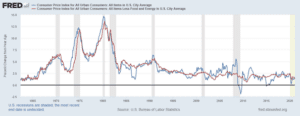

Inflation in the US right now, as measured by the Federal Reserve, is extremely tame. Annualized inflation for the Federal Reserve’s All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average Consumer Price Index is currently at 1.7 percent. While this reading is the highest in the last 12 months, the rate is still below the Fed’s target of 2 to 2.5 percent for a sustained period. When we strip the more volatile food and energy components from this index and get down to what’s referred to as “core inflation,” we see an even tamer reading of 1.3 percent annualized (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Consumer Price Index Rate of Change, 1962-2021.

If we put the most current readings for inflation and core inflation in the context of the last 60 years of data, the current readings are in the bottom 23 percent of all readings for general inflation and the bottom 8 percent for core inflation. In short, inflation is historically low right now using both indicators, but it’s higher when we account for food and fuel. Inflation in these areas is not unexpected given a strengthening economic recovery, supply disruptions (food), and supply reductions (fuel). I can hear the argument in my head now that 60 years is too long a period and that I should use something more recent so let’s look at current inflation data through a 30-year lens. Through the 30-year lens, current inflation readings are in the bottom 31 percent of all readings while core inflation is in the bottom 7 percent of all readings. So, by both these measures’ inflation is currently in-check with room to run to hit the Fed’s desired 2 percent minimum level.

Will the American Recovery Plan Act cause inflation?

Yes, it likely will and, frankly, that’s part of the point of the Act. The idea is to stimulate an economy where employment is at 6.3 percent and where economic damage has been concentrated in the households who make up the bulk of basic economic spending. There is an increasing belief in the Federal Reserve that a period of somewhat increased inflation would be good for wage earners who have haven’t seen significant wage increases in several decades. While we’re not seeing a trend of increasing core inflation we are seeing more discussion of inflation and discussion of individualized examples of inflation where supply constraints combined with more cash resources are driving prices higher. Some of this chatter is reporters reporting on the hot topic of the day, but we still should be aware of the stories they tell.

Could inflation increase to the point where it could be disruptive?

The point of both stimulative monetary policy (i.e., low interest rates) and stimulative fiscal policy is to increase economic activity and raise inflation a certain amount. It is possible that policy makers will overshoot and overheat the economy, but the U.S. economy hasn’t overheated in this manner in a very long time. Plus, we really haven’t seen significant inflation in the U.S. since the 1980s. Additionally, by all traditional measures there is slack in our economic system via unemployment, underemployment, and a lack of labor force participation. Where I think inflation could become an issue in the non-investment environment is if energy prices rapidly increase and crimp discretionary spending just as the economy tries to take off. (Note: You may have noticed a recent increase in prices at the gas pump). This situation is in part would create 1970s style “stagflation” where the economy stagnated, but energy prices grew. The U.S. economy is much more energy efficient now than it was in the 1970s and large parts of the country experience a net benefit from an increase in energy prices including our home state.

Jonathan’s Takeaway: In the short-term Jonathan is not concerned about inflation in the general economy. However prospects for higher inflation will increase later this year and in early 2022. Should inflation rise about 2.5 percent for a sustained period he expects that the Federal Reserve would take appropriate action and raise rates. The Fed has struggled to stimulate inflation to the 2.0-2.5 percent level for several years so until evidence presents to the contrary (and outside of interest rate sensitive investment vehicles) the economic risk remains with getting the economy moving again rather than creating an inflationary environment.

Jonathan King is a consulting economist and Certified Professional Coach. His firm, Halcyon Consulting, is dedicated to helping clients reach their goals through accountability, integrity, and personal growth. Jonathan has 24 years of social science consulting experience, including 17 years in Alaska. The comments in this blog do not necessarily represent the view of employers and clients past or present and are Jonathan’s alone. Suggested blog topics, constructive feedback, and comments are desired at askjonathan@apcm.net.